In my humble few years reading detective fiction, I have come to think that Edmund Crispin is a fairly underrated writer. His word play and illustrious flourishes of language – that are able to move the plot and not stall it – are second to very few. His books are a delight to consume, and his ability to use an unexpected but satisfyingly accurate word or phrase shows a command of the english language fitting for his status as an Oxford grad.

This also makes his writing style extremely musical. The prose are crafted as to carry you along as if on some kind of linguistic/melodic wave. This is fitting as Crispin, real name Bruce Montgomery, was also an established composer, so his works are steeped in the appreciation of music and composition. It is also potent for this review of Swan Song, his 4th book penned in 1947, an impossible crime novel set in and around the Oxford opera house and its multi-various cast.

The hilarious opening chapter sets the novel off at a solid pace, telling the tale of the awkward love between Elizabeth Harding and Adam Langley. We then see much of the novel through their eyes, Elizabeth as a journalist, writing a piece on the great detectives (Sir Henry Merrivale, Campion and Mrs Bradley all getting a mention) and Adam as a tenor in Die Meistersinger, a three act operatic drama composed by Wagner being staged in Oxford.

The book then flies through the meeting of our cast of voices, composers and stage hands, tension horribly rising until singer and tyrant Edwin Shorthouse, after causing trouble for almost everyone involved, is found hung in his dressing room. The evidence points in many strange directions, and when Crispin’s series detective, Oxford don Gervase Fen, arrives on the scene he unwillingly pronounces murder. However, after Shorthouse entered, the room was watched the entire time, leaving no opportunity for anyone to enter, hang the victim, stage a suicide and leave, without being seen.

Suffice to say I thought this book was wonderful, the pace plotting and clueing are just right, and the cast of characters are of the classic Crispin ilk, richly observed, memorable, touching, laugh out loud, with some of the bit part players having the most hilarious parts to play. I mean how can you not love a disreputable homeless criminal, helping Fen break into a house, on being disappointed that there is nothing to steal saying ‘What we want is socialism, so as everyone ‘ll ‘ave somethink wirth pinching…’

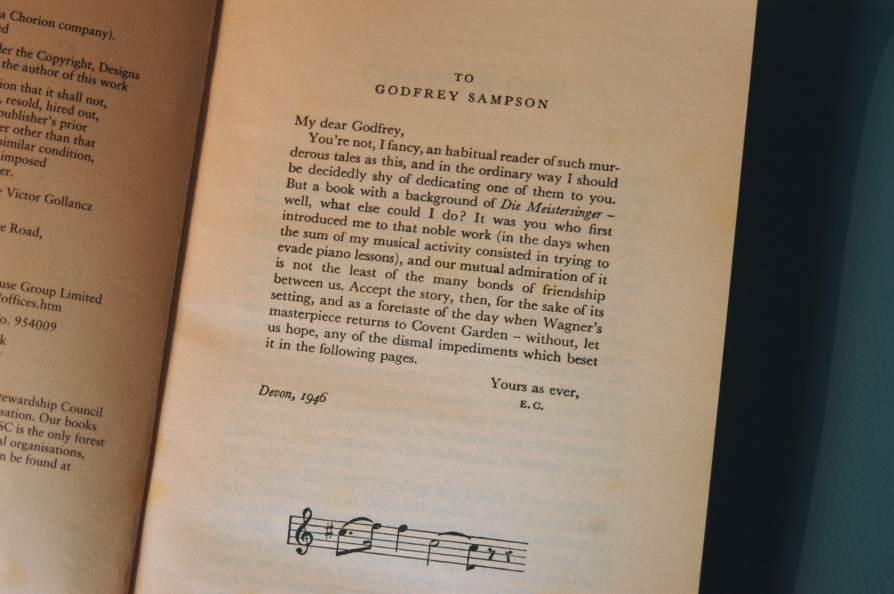

If you think the idea of a mystery set around the opera sounds achingly boring, fear not, as the book is really a sly satire on the culture of the opera house and the academic world of the Oxford don. Much of which feels like a forerunner to the satirical writing of the likes of Woody Allen on these same themes. Note for example the similarity of the laugh out loud conversation between a group of ‘young intellectuals’ in the queue for the opera in chapter 22, to the conversation in the queue for the movie theatre in Annie Hall. It’s Crispin’s inside knowledge and respect of these themes that allow him to manage the satire in such an offhand and satisfying manor. Swan Song acts as much as a love letter to the opera, as well as a detective novel. This is evident in the dedication page which includes a small notation from Die Meistersinger itself.

Other highlights include chapter 11 which waxes lyrical on the atmosphere of Oxford in the low season, with gorgeous descriptions of lonely objects and places, without being over bearing. This same chapter then takes a snap turn with an unexpectedly dark event, rapidly moving the plot forward. And chapters 21 and 22 manage to recapitulate everything we have read, adding pause for consideration of all we have seen, without it feeling at all forced, this is a very difficult thing to pull off. Chapter 21 feels ahead of its time, almost like it could have been written for screen.

To speak of the impossible crime, the problem is neat, simple (pretty dark) and believable, but definitely guessable to the seasoned reader. The identity of the killer however is a real hidden gem, and a great twist, turning the events of the book on their head.

So if you are new to Crispin or want to try something more, I highly recommend Swan Song, or The Case of The Gilded Fly, another of his impossibles which is set around the theatre. The humour, and solid detection will be no end of pleasure.

Given the amount of overlong and dissatisfying novels I’ve read of late, it’s fabuous to be reminded of this and its pared-back brilliance — not one wasted word, not a single chapter of filler, just a great plot, executed swiftly, and cleverly resolved. I spotted the killer but not the method, which puts us the opposite way around from each other; I wonder what it is that makes someone see an entirely different thing in the exact same words? Reading’s weird like that, innit?

Glad you enoyed this, especially as Crispin takes something of a dive from hereon out. Love Lies Bleeding is…passbale, but the others ae hard yards. How bad are they, you want to know? Well I read Frequent Hearses for a second time without realising I’d read it before until I got to the end…

LikeLiked by 1 person

So glad you enjoyed this one as much as I did. I got thrown off the killers sent by the bloody removing cream! (I had other false ideas about it which were leading me astray). There were certain elements that meant to me that it could only be that solution to the watched room, but I won’t go into them here at the risk of spoilers.

And what a sad comment for Frequent Hearses. What is it about these later works do you think that doesn’t work?

LikeLike

Well, I mean, in a nutshell: everything.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Oh man, the reader is indeed warned!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Glad you like Crispin’s work too. His humour is brilliant. The first 6 books are the ones where Crispin works at his best. After that quality does drop with books such as The Glimpses of the Moon, Frequent Hearses and Beware of the Trains, though The Long Divorce is not too bad. Been about 4-5 years since I read his work but The Moving Toyshop and Buried for Pleasure are my favourites, if my goodread records are reliable.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Kate, really glad you are on board with Crispin too, he is such a delight. It seems this feeling about drop in quality is a common one (see JJ above). I haven’t read any of these later ones, but do have Beware of the Trains and that contains one of my favourite locked room shorts ever The Name on The Window, but I can’t confess to reading or remembering the others, so your point still stands!

Haven’t read Buried for Pleasure either but excited about that one now you have said its a favourite. I loved Moving Toyshop, though it’s always billed as an important impossible crime novel, but I’m not sure the solution really means that it is one, even if the set up suggests it is? I like the meta elements of Toyshop as well, which was my first encounter with that type of thing.

LikeLike

Thanks so much for the review. 🙂 I’ve ‘Swan Song’ sitting on the TBR pile, and it has been set apart as Crispin’s final outing for me, given my principle of ‘Best for Last’. Thankfully, I still have ‘Moving Toyshop’ and ‘Holy Disorders’ (as well as ‘Buried for Pleasure’ – if I can get hold of it on Kindle) to get through first. I also have ‘Frequent Hearses’, ‘Long Divorce’ and ‘Glimpses of Moon’ on my Kindle, but the comments by other bloggers have not been encouraging…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes those later ones seem to be much out of favour. Really hope you enjoy it when you get to it, it is brilliant.

How about Gilded Fly? Moving Toy Shop is a great high paced one too, with some gorgeous clues.

LikeLike

I’ve read ‘Gilded Fly’ and ‘Love Lies Bleeding’, and I liked the latter more because my favourite character appears in it. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hmm, not read Love Lies Bleeding, but have it. Must get to it!

LikeLike