Ah, what a joy to be back in the midst of Carrian plotting, atmosphere and cunning. In a brief hiatus on the blog to sort out some bits in what we call ‘life’, I have had some time to squeeze in a few marvelous mysteries. And now I am back in the blogging world with the first of a three-parter that I am giving over to another of Carr’s unexpected treasures, Death Watch.

Written in 1935 Death Watch sits between Plague Court and White Priory on one side, and straight after we have The Hollow Man and Red Widow. So Death Watch comes at pretty poignant time in Carr’s career, surrounded by such giants of his work.

I wanted to get to this book specifically after finding such a lovely Penguin copy (pictured above) in Black Gull books Camden on my second hand book walk. And also as Ben from the Green Capsule had peaked my interest when we recorded our Men Who Explain miracles mega-double-whammy podcast episode on the stages of Carr’s career.

To me Death Watch sits curiously in Carr’s ouvre and feels like we have been watching a master magician come off the stage after an amazing show, and then backstage proceed to show you some fresh, intimate, cutting edge tricks he has been working on. Tricks that he wouldn’t put in the main stage show, because they are a little out there and ahead of their time, but that pile on the ingenuity in fresh ways. If that makes sense?…. No? Let’s move on.

I’m going to take a different approach from the normal review. There are some great right ups in the bloggersphere (links at the bottom) if you are interested to see what Death Watch is all about. For this first post of three I’m going to talk about what I believe are a number of internal secrets that I have spotted in a second reading of Death Watch. In particular the use of architecture in the book, and more specifically the homage to one British architect, the great John Soane. Now before you yawn and close your laptop/phone screen stay with me. I propose that this singular relationship to John Soane and his now famous museum in central London, are like a secret backbone, weaved through the book that helps us to see the text in a new light. Let us begin.

The House that John Built.

John Soane (1753-1837) was a British architect most famous for designing the huge Bank of England building and Dulwich Picture gallery, the first art gallery in the world. He was the head of architecture at the Royal Academy and through his life he amassed a huge amount of sculptural, artistic and architectural artifacts which he displayed in a beautiful and intricately purpose built interior, which stretches across two houses, now open to the public and known as the John Soane Museum. If you’ve never been you have to go.

Why is this important? Well, Carr’s Death Watch is set almost entirely in a single, large house. This house is stated in chapter one as being number 16 Lincoln’s Inn Fields. The John Soane Museum is (in real life) situated at number 13 Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Dr Melson, our young, tag along british side kick to Dr Fell in this case, makes direct reference to the museum in chapter one and the chapter is even called An Open Door in Lincoln’s Inn Fields. Carr wanted us to notice this.

And there is more. Take for example, one of the first detailed descriptions as we enter the household of Johanus Carver, watch and clock maker of Death Watch. Notably, the staircase. This staircase will be heavily featured, playing vital roles in the tale, and is described by Carr with a beautifully sinister bite:

It was a prim stairway, with heavy banisters, dull-flowered carpet underfoot, and brass stair-rods; it was a symbol of solid English homes, where no violence can come, and did not creek as they mounted it.

It is also described in chapter three as being if a reddish flowered design carpet that runs into the corridors. Compare those descriptions with the main staircase in the John Soane museum (pictured below) and you’ll get where I am going with this.

Coincidence? Let’s continue. After this detail the most telling aspect for me is the room in which the victim is found splayed across the threshold. This room is described as being filled with dark wooden book shelves that cover the walls, Morris chairs, a deep leather couch and high backed Hepplewhite chairs. Look at John Soane’s living room and the similarities abound.

At this stage you could say that this is Carr simply referencing or that many houses could have had these items. But Carr takes it a step further. Their is a notable difference in the living room of Soane and the room of Death Watch where we find our victim: the bookshelves are only shoulder height rather than ceiling height. This is because hung above them, Carr tells us that copies of the famous series of oil paintings The Rake’s Progress by the English painter William Hogarth. This is important. Famously the Soane house and new museum contains the entire original eight paintings of The Rake’s Progress in a purpose built room, and this for me is where the comparison gets really interesting.

Artworks feature heavily in Carr’s works, and by including The Rake’s Progress, Carr takes a step from visual and atmospheric inspiration, to using the structure and meaning of the Soane museum to drive the plot.

In fact I am proposing dear reader that Carr stood in the room of the John Soane Museum where The Rake’s Progress series is hung and the structure of Death Watch was built in his mind.

I say this for two reasons. Firstly The Rakes Progress, and how one encounters these paintings in within the architecture of the John Soane Museum, is essentially linked to the plot of Death Watch.

Secondly, and for me what makes this whole relationship between Soane and Carr so good, is that The Rakes Progress is a narrative set of paintings, a narrative that Carr uses as a bedrock for his characters in Death Watch. I can only say so much here, but the traditional character of the ‘Rake’ (or a ‘Rakehell) and his journey through the paintings is mirrored in a number of the characters and their journey through the plot of Death Watch. Carr’s book is a subtle but powerful nod of thanks to John Soanes, his home and his collection. Interesting right? (Well it’s been fun for me!)

More historical ‘movements’:

Here’s a few more little historical gems that reveal themselves:

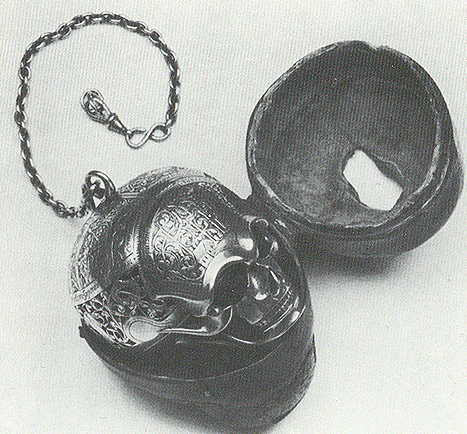

The titular ‘Death Watch’ of the book is taken, as Carr states in his very tongue in cheek prologue, from a description he saw in a clock makers reference book: F.J.Britten’s Old Clocks and Watches and their Makers, published in 1932, probably just as he was writing Death Watch. I have since found that book and here are the illustrations of the ‘Death Watch’ itself.

These watches known as Memento Mori watches were made by a mysterious French watch maker known only as ‘Moyse’. The one used in Death Watch was owned by Mary Queen of Scotts, and the same narrative runs in Carr’s story. In real life the watch was given to one of Queen Mary’s ladies in waiting, Mary Seton. The name Seton will jump out to many Carr obsessives, as being the surname of one of Carr’s most vital career characters, Fay Seton from He Who Whispers.

That book is set in a small fictional french town near Chartris, very similar to the french town of Reims where Mary Seton finished her days as a nun, and where the watch was discovered. (I could be reading into things here too much but I’m enjoying myself dammit!)

– Soane had many clocks in his collection, spread out in different rooms, and a number of clocks and the way they are shown in Death Watch match those in the Soane collection.

– In the third painting of The Rake’s Progress, Tom ‘the Rake’ is having his watch stolen by a women at a fancy party. The opening crime in Death Watch is a unsolved murder in which a woman has killed a man and stole a famous watch.

– The pub at which many of the cast of Death Watch hang out is called the Dutchess of Portsmouth. This pub doesn’t exist but the next road on from Lincoln’s Inn Fields is Portsmouth Road, named after Dutchess of Portsmouth, one of Charles the II’s mistresses.

– Charles the II housed the Dutchess in a property on the corner of what is now Portsmouth Road, this house subsequently became famous for being the so called ‘Curiosity Shop’ that features in Charles Dickens famous work Master Humphries Clock, which, wait for it, is a bout a story teller who keeps his manuscripts locked inside an ancient clock. Clocks, watches, time pieces, they are everywhere!

Times running out!

Okay okay, I’m possibly overstating my findings here. But what I love about all these links I am drawing out, is being given what I feel like is a secret window into the mind of the master himself. Where Carr found his inspiration has always been an interest to me as his ideas and settings were so diverse. Here we can imagine him at the John Soane house, surrounded my incredible artifacts, architecture and paintings and the cogs start turning as plot lines and impossible mechanisms fall into place like the beautiful structure of a rare skull-watch.

See you in part two.

From other bloggers:

Ben at – The Green Capsule

JJ at – The Invisible Event

Kate at – Cross Examining Crime